If you've ever walked away from a loud concert with a temporary buzz in your ears, you've had a taste of tinnitus. For most people, it fades quickly. But for millions, that phantom noise, ringing, buzzing, hissing, or roaring, sticks around, sometimes becoming a daily struggle. It's not a disease on its own, but a symptom often tied to hearing damage, exposure to loud sounds, ear issues, or even stress and health conditions. Around 10 to 15 percent of adults experience some form of tinnitus, and for about 2 percent, it's severe enough to disrupt sleep, focus, and overall well-being.People usually describe it as subjective, meaning only they hear it, though rare cases are objective and can even be picked up by a doctor.

Where Does Tinnitus Really Come From?

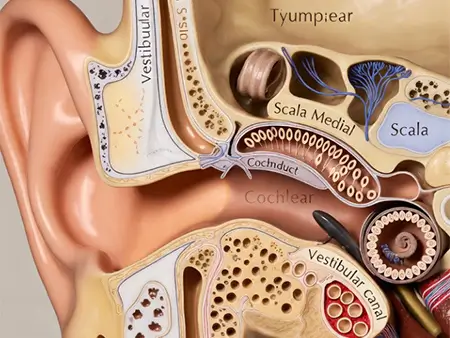

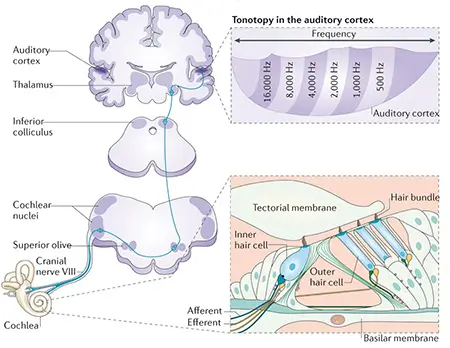

A lot of folks think the noise is right in their ears, but it's more complicated. The trouble often starts in the inner ear, specifically the cochlea. That's where delicate hair cells pick up sounds. Loud noise, aging, or certain medications can damage these cells, especially the outer ones that boost faint sounds. When they're gone, the signals to the brain get messy, leading to extra random firing along the auditory nerve. But here's the key: the ringing you actually "hear" happens in the brain. With less normal input from the ears, the brain cranks up its sensitivity, turning background neural noise into something noticeable. It's like the brain filling in the gaps, but in a way that creates phantom sounds. Brain scans show heightened activity in auditory areas, plus involvement from regions handling emotion, attention, and memory, like the limbic system, which explains why stress can make it worse.

The illustration highlights damaged hair cells in the cochlea and how that leads to overactivity in brain networks.

What's New in Tinnitus Research?

Scientists have made real progress lately, moving beyond just masking the sound to targeting brain changes. For instance, bimodal neuromodulation—combining tailored sounds with gentle tongue stimulation—has shown strong results in trials, with many patients reporting significant relief. Devices like Lenire have gained approval based on studies where people improved after weeks of use.

Other exciting work includes spotting objective signs of tinnitus distress, like subtle facial twitches or pupil changes when exposed to annoying sounds. These could finally give doctors measurable biomarkers to test treatments properly.

There's also fresh insight into sleep's role: deep sleep seems to naturally dial down abnormal brain activity linked to tinnitus. And sound therapy experiments, where customized tones disrupt noisy brain patterns, are proving effective without placebo effects.

Researchers are exploring everything from cognitive behavioral therapy apps to brain stimulation, and even how speech understanding ties into tinnitus loudness. All this points to better, more personalized options ahead, sadly no cure yet, but real hope for managing it effectively.

If tinnitus is bothering you, see an ear specialist or audiologist. Simple steps like sound therapy, hearing aids, or stress management often help a lot.

You could also consider finding out more about audio masking for tinnitus where specific frequencies are played at low volume in a headset, to help mask the tinnitus sound you are hearing.